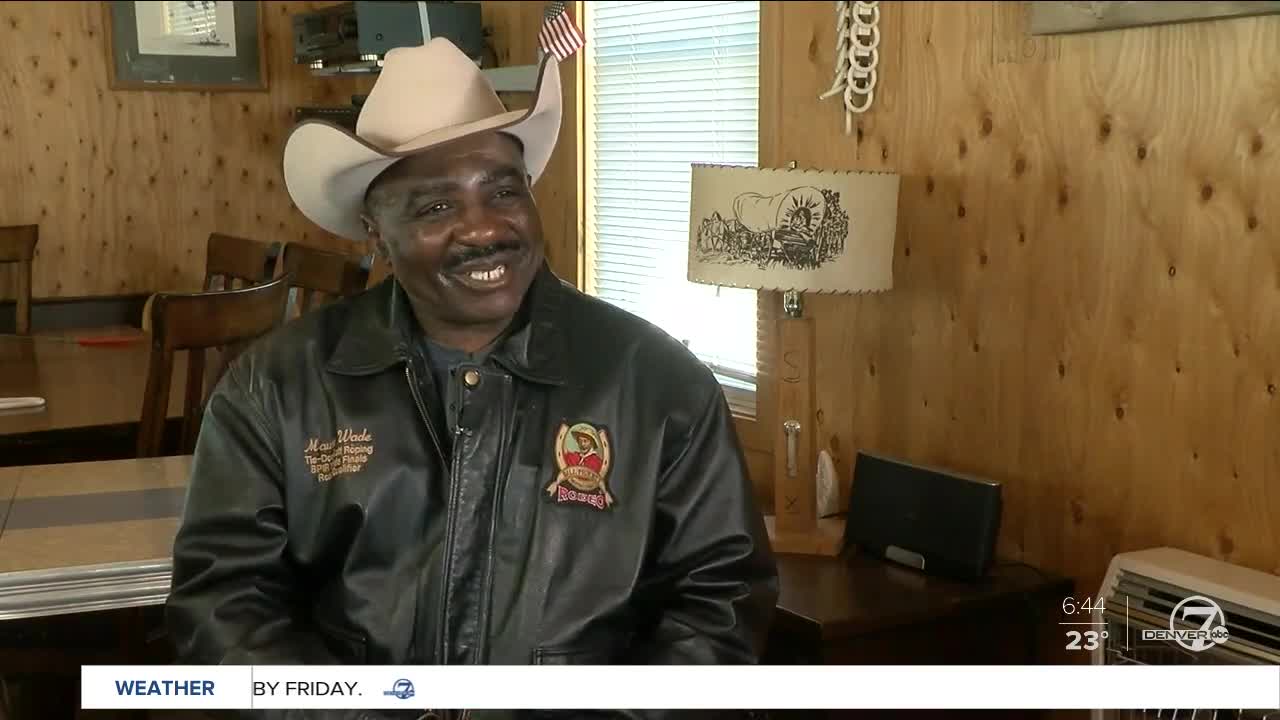

ADAMS COUNTY, Colo. — Every morning, professional rodeo cowboy Maurice Wade makes his way to a ranch in Bennett, Colorado where he feeds his hungry and waiting horse, Beer Money.

“Everybody asks me, ‘Why did you name your horse Beer Money?’" he said. "I told them, the only money you’re going to win in rodeo is enough money to buy a beer and a hamburger."

Wade is one of the only black professional cowboys who competes in professional rodeos.

“It was something that I wanted to do all my life,” he said.

Wade’s story starts on a farm his grandfather owned in Mississippi.

“Back when I was coming up, that was in the 50s, our heroes were cowboys," he said. "I used to pretend when I was kid. We rode stick horses."

Years later when Wade came back from fighting in the Vietnam War and started working for the U.S. Government in Colorado, he realized his pretend horse was a catalyst for something very real.

“I met this gentleman by the name of Henry Lewis — he was an old black cowboy who’d been around Colorado forever,” Wade said.

He said growing up, he never saw a cowboy that looked like him and thought he would become the first black cowboy. Until he met Lewis.

“He roped calves and I used to go over to help him and practice," Wade said. "One thing led to another and I started meeting other people in the business and the next thing I knew I had a rodeo rig, I had

horses, and I was roping."

Wade said as he got more into rodeo life another one of his mentors, Lu Vason, wanted to create a space for black cowboys to come together.

“Lou was at Cheyenne Frontier Days, and he didn’t see a black cowboy," Wade said. "He did a lot of research with Paul Stewart as the founder of the Black American West Museum to find other black cowboys."

Terri Gentry, a volunteer docent at the Black American West Museum in Denver, said in the height of the profession, Stewart discovered one in three cowboys were black.

“That was one of the reasons why he started this museum,” Gentry said.

“When slavery ended, it continued to be a vocation for quite a few African American men and their families. It was a hard life to live,” Gentry said.

Gentry said being a cowboy was a way for black men to support their families away from some of the discrimination and racism that were more present in other industries.

But cowboys still faced some racism.

And to this day, a lot of their contributions go unrecognized.

“Unfortunately, we’ve become invisible in a lot of different facets,” Gentry said.

But Gentry said the museum will always display the cowboy's accomplishments and continued success.

“There are some local black cowboys that we work with now such as Maurice Wade,” said Gentry.

The research from Lu Vason — Wade's mentor — paid off and he eventually found a space for active black cowboys to get together — the Bill Pickett Rodeo.

“As a result of the Bill Pickett Rodeo, a lot of black cowboys started coming out,” Wade said.

Every year, during the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, the Bill Pickett Rodeo makes a stop at the National Western Stock Show.

Wade said he hopes that future black cowboys and cowgirls will see the rodeo and professionals like him, and know that there is and has always been a place for them in this profession.