News 5 Investigates is asking state officials why it took years to shut down the troubled El Pueblo Boys and Girls Ranch after we discovered numerous cases of abuse and neglect at the facility.

Over the years, El Pueblo was home to hundreds of children and teens with psychiatric and behavioral issues.

An open records request News 5 submitted unlocked several abuse and neglect violations documented in 2013-2017 state inspection reports that were not publicly released until we asked for them.

“I do not want this place ever opened up again so I was very happy,” Lisa Mitchell told News 5 in an interview last month.

Lisa’s son, Sam, spent several years at El Pueblo. His mother said he suffered a traumatic brain injury at birth and struggled in school. After suffering severe mood swings, Lisa sought help for her son.

At the age of 11, a court ordered Sam to live at El Pueblo—little did Lisa know what would happen behind the brick walls at the facility.

“I feel it was so concealed,” Lisa said. “It was like a secret.”

The secrets hidden behind closed doors were revealed after El Pueblo had its license suspended.

News 5 found case after case of abuse and neglect involving staff members physically kicking and kneeing children.

On multiple occasions, state inspectors said El Pueblo staff didn’t appear concerned about the care and well-being of children in their custody.

Children also complained about being hungry. In one report, a child lost a considerable amount of weight and no one from El Pueblo could explain why.

Staff also lost medication, gave children wrong medication and failed to notify a parent after their child ran away from the center.

“I got knee striked and female staff would pinch me,” Sam said when asked how he was treated at El Pueblo. “Some staff would choke me to the point that my face was blue and I couldn’t breathe.”

Sam says as some staff members would physically assault children, other employees ignored the problems.

State inspectors confirmed El Pueblo staff failed to report suspected abuse and neglect cases to DHS, which is required by law.

“Your tax dollars went to fund this (operation), Lisa said. “You funded child abuse.”

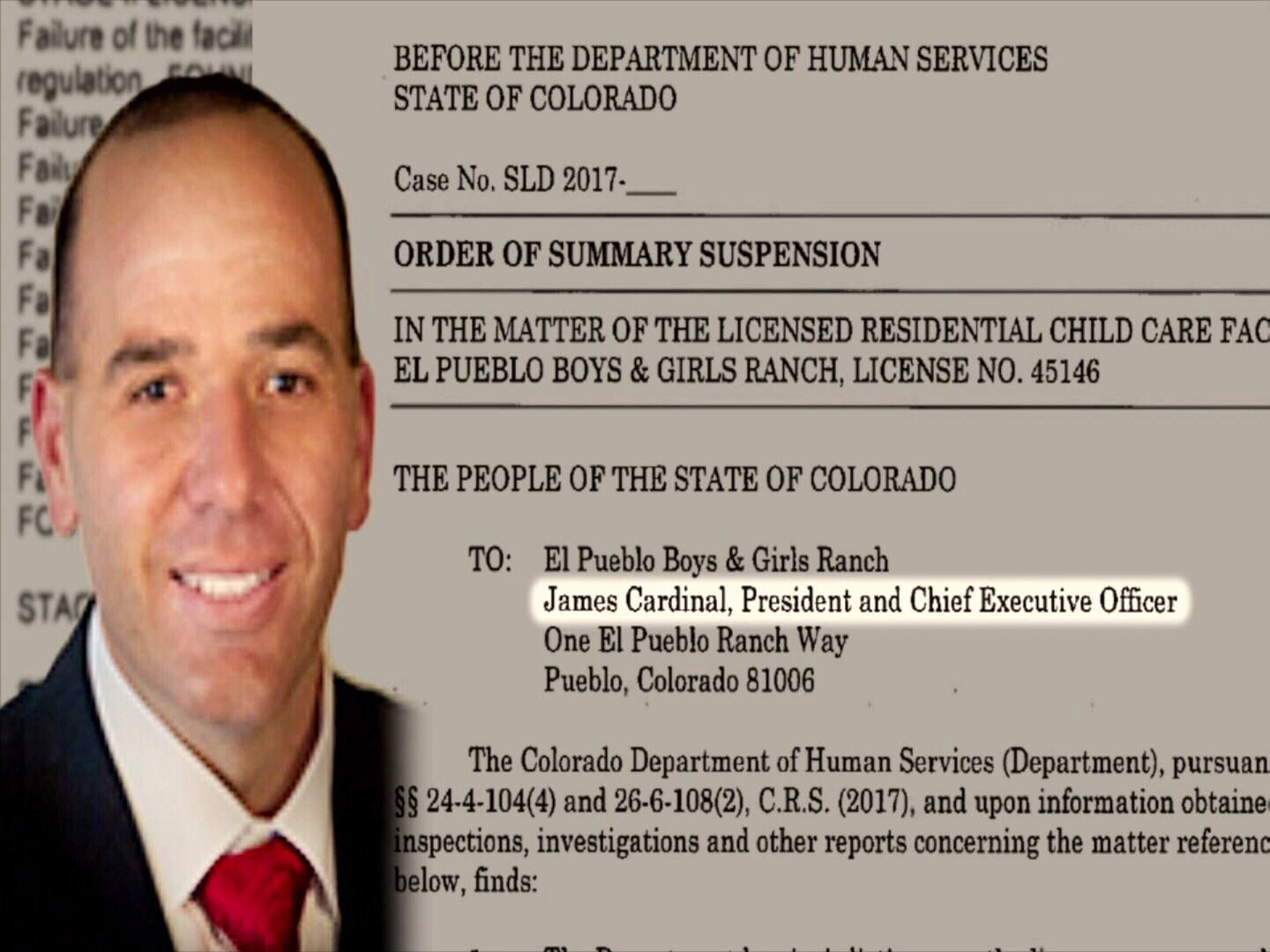

News 5 Investigates uncovered El Pueblo CEO James “Jimmy” Cardinal was even caught covering up the abuse. In a 2017 suspension summary report, Cardinal inappropriately restrained a child and then submitted false information to the Colorado Department of Human Services when asked about the incident.

“When we were seeing a pattern of untruth, unwillingness to cooperate, unwillingness to adhere to rules, that is when we took adverse action and suspended their license,” Minna Castillo-Cohen, the CDHS Director of the Office of Children, Youth and Families said.

However, El Pueblo’s license wasn’t suspended until Sept. 2017.

“In state inspection reports, there was a history of violations that occurred over and over again,” Chief Investigative Reporter Eric Ross told Castillo-Cohen. “This abuse has been documented for years, but there were no consequences?”

“When we are working with a facility, it’s really important to understand whether we working with a struggling good actor who is capable of making those changes, or are we working with someone who is unable and unwilling to make those changes,” Castillo-Cohen said.

Castillo-Cohen says when violations are documented, their goal is to give the facility time to respond and correct problems first. Suspending or revoking a license is a last resort.

“We don’t want to re-traumatize kids by just going in and closing a facility,” she said. “There are placement disruptions that can be very traumatic to children.”

However, parents like Lisa argue being abused in neglected is also traumatizing.

“I don’t know who is going to hold them (El Pueblo staff) accountable but we demand a grand jury,” Lisa said.

Ross asked Castillo-Cohen, “Has any El Pueblo employee been arrested and charged with child abuse or neglect?”

“Not to my knowledge,” Castillo-Cohen said.

Ross responded, “If any parent did what some of these El Pueblo employees did to children, they would likely be behind bars.”

“I am unaware of any employee at El Pueblo that had criminal charges pressed against them,” Castillo-Cohen said. “I think you can take that up with local law enforcement.”

In cases where staff members admitted to physically assaulting or abusing children, they were either terminated or quietly resigned.

Ross asked, “What do you tell parents who say the State failed their children and failed them?”

“I would say to parents that we care deeply about all children in our state,” Castillo-Cohen said. “What happened at El Pueblo was deeply, deeply saddening to us and we want Colorado families to know that we are working tirelessly to prove our processes.”

In 2016, CDHS switched over to an annual inspection system. Prior to that, CDHS used a risk-based assessment for inspections.

El Pueblo was on a 2-year inspection cycle. However, Castillo-Cohen says that would not have prevented county DHS workers to do unscheduled visits as a result of a complaint.